- Published on

Integrating Boston’s Public Schools: The Busing Controversy in the 1970s Learning from the Crisis

- Authors

- Name

- Yuxue Zhao

Catalog

Integrating Boston’s Public Schools: The Busing Controversy in the 1970s Learning from the Crisis

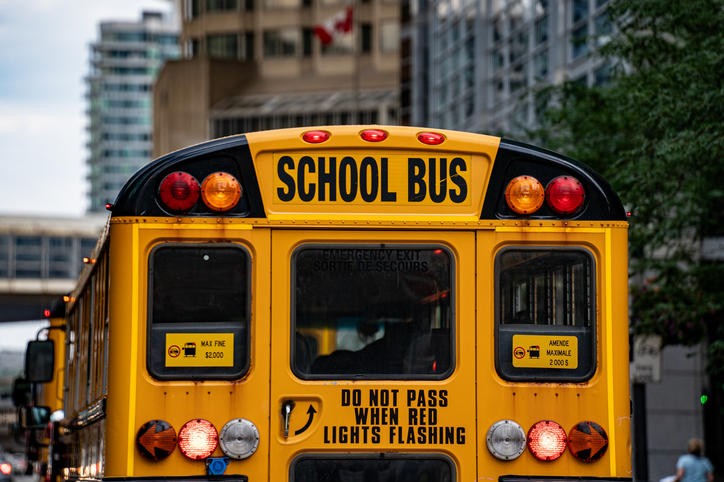

Despite the Civil Rights Act of 1964 signaling a commitment to end segregation, Boston’s busing crisis in the 1970s illustrates the complex and often contentious nature of implementing such policies at the local level. Court-ordered forced desegregation was necessary due to the Boston School Committee’s lack of cooperation and blatant disregard for constitutional mandates. This intervention, led by Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr., marked a significant step toward racial integration in education. In this essay, I will briefly discuss the outcome of Boston’s busing and its dominant reasons. It’s crucial to understand that Boston’s busing, while controversial, cannot be simply labeled as a failure or success in the city's history; it was a complex endeavor that exposed the deep-rooted tensions and challenges of enacting societal change.

Bostons busing achieved complex results. On one hand, it was successful to some extent in achieving racial integration of the students in Boston. More precisely, it managed to get some white and black students to attend the same schools, albeit alongside inequality and conflict, fostering initial contact between black and white students. It urged people to take civil rights seriously and, within the global context of that era, pushed for the issue of civil rights in the United States to be recognized and tackled by its leaders (Patterson, 2002, pp.7-9). It propelled the first black individual John O’Biyant to become a member of the Boston School Committee; it also inspired the women’s rights movement (Formisano, 1991, p. 147). On the other hand, as a policy of racial integration, it was thought to have failed. Because it did not fundamentally achieve the goal of racial integration and appeared to exacerbate racial segregation, such as black-white violence and the white flight. Busing acted as a catalyst, transforming the submerged racial discrimination and class conflict in the lives of Boston’s residents into overt violence, plunging the city into chaos. Additionally, students, the group that should have been the primary concern in busing, were neglected, intimidated, and “stoned”. Busing, intended to improve education quality for blacks, backfired, and the adult conflict was transferred to children, who turned against each other. Amidst the chaotic social backdrop, the youth were more prone to adopting vices such as drug abuse and crime. A grain of sand in history becomes a mountain when it falls on an individual, and the students impacted by busing, whether white or black, were all traumatized in one way or another, yet no one has apologized or made reparations to them.

The busing policy itself was flawed, as the black community’s demand was for equitable education, yet Judge Garrity opted to use busing—originally a strategy utilized in Operation Exodus —as the primary means for court-mandated educational racial integration. This decision is intriguing. However, do all the outcomes stem solely from busing? No. Busing is merely a facade, the real underlying causes are complicated. I will discuss three causes of that: inherent class issues, the hypocrisy of Boston politicians, and the media’s unfair reporting.

Firstly, the most significant issue with this policy is its reflection of classism, excluding the upper class from its scope. Boston’s busing movement, which was confined to inner-city districts and bypassed the suburbs and private schools, affected only the lower class while sparing the affluent upper class, perpetuating the American customary approach to social issues. As lower-class whites and blacks were left to grapple with this racial integration policy, fearing for their children’s daily school life, upper-class whites were able to enjoy a serene and untroubled existence in their pristine suburban neighbourhoods, detachedly observing the unfolding drama among the lower classes. “The ultimate reality is the reality of class, having and not having, social and economic vulnerability versus social and economic power—that's where the issue is(Tager,2001,p. 227).” Therefore, class is the root of many social issues. If upper-class whites had been included in Boston’s busing, the initiative might have been quashed by those affected upper-class from the start.

Secondly, Boston’s busing faced multiple obstacles in its implementation, including from Boston’s politicians and civils, stemming from the beliefs—that they did not recognize the existence of racial discrimination in Boston, they thought that “unlawful segregation and racism were exclusively a southern phenomenon (Delmont, 2016, p. 13)”. The most significant was the obstruction from politicians, where forces that should have been allied were hostile to each other, such as the vile obstruction from the Boston school committee, and Mayor Kevin H. White’s vacillations, making the implementation of busing especially difficult. In this process, the ugliness of politicians playing with power was unquestionably revealed, with politicians exploiting the chaos for fame and fortune, like Louise Day Hicks, who led the school committee to delay addressing the structural issues that led to Boston’s Busing Crisis by opposing school desegregation throughout the 1960s (Delmont, 2016, p.16). Politicians continued to stir up public emotions and promote fear of busing to secure their political careers. Besides, there were also obstacles from the Boston underclass, including strong protests from both whites and blacks, and violent clashes between the two, adding to the practical difficulties of implementing busing. White working-class, angered by resources being diverted to incoming ethnic groups, launched various anti-busing movements. In contrast, blacks, incensed by a long history of unfair treatment, responded to provocations from whites and even initiated attacks. Tager(2001) revealed the common reason for their violence “They felt either deprived of full participation in society, and therefore powerless, or that their future expectations bore little hope of realization. (p. 228)” Consequently, believing their grievances could not be addressed through legitimate channels, they resorted to violence.

Finally, the media played a significant role in fueling the controversy surrounding the busing process by emphasizing stories about the fear of busing, thus exacerbating the already turbulent atmosphere in Boston. The coverage tended to focus on the anti-busing sentiments among white Bostonians, which were deemed more newsworthy and visually appealing for television journalism. This focus on sensationalism often came at the expense of moral or political considerations, as noted by Delmont (2016, p. 14). As a result, the media disproportionately highlighted resistance to busing from the perspective of white communities, while the views and experiences of the black community were largely overlooked. Important issues such as life in the ghettos, everyday hardships, and the grievances of black residents received scant attention. Politicians, exploiting media coverage, were able to present biased portrayals of busing, frequently framing it as an act of “coercion” and portraying the policy as rash and ill-conceived. Delmont (2016) critiques this approach, stating, “Television news broadcasts were not designed to produce deeply researched reports, and they were particularly ill-equipped to present complex stories like school desegregation, which involved law, education, politics, social science, and history. (p.14)” Which highlights the media’s role in simplifying and skewing the narrative of school desegregation, contributing to the obstructing a nuanced understanding of the issue.

In conclusion, the Boston busing initiative of the 1970s, aimed to break down the entrenched barriers of racial segregation in schools, which was more than just an educational policy but a reflection of the broader civil rights struggles, class disparities, and racial tensions simmering beneath the surface of American society. The outcomes of busing, a blend of progress and setbacks, hope and disillusionment, unity and division highlight the nuanced journey of societal transformation. As Theoharis (2015) insightfully notes, “Busing didn’t fail; the nation’s resolve and commitment to equal and excellent desegregated schools did.” The story of busing in Boston transcends a simple narrative of success or failure. It represents a pivotal chapter in the history of civil rights, showcasing the bravery required to challenge injustices and serving as a poignant reminder of the complex path toward racial integration and equity.

References

Delmont, M. F. (2016). Why busing failed: Race, media, and the national resistance to school desegregation. University of California Press.

Formisano, R. P. (1991). Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. University of North Carolina Press.

Patterson, J. T. (2002). The troubled legacy of Brown v. Board. In African-American Studies at the Woodrow Wilson Center (pp. 4-12).

Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Theoharis, G. (2015, October 23). ‘Forced busing’ didn’t fail. Desegregation is the best way to improve our schools. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2015/10/23/forced-busing-didnt-fail-desegregation-is-the-best-way-to-improve-our-schools/