- Published on

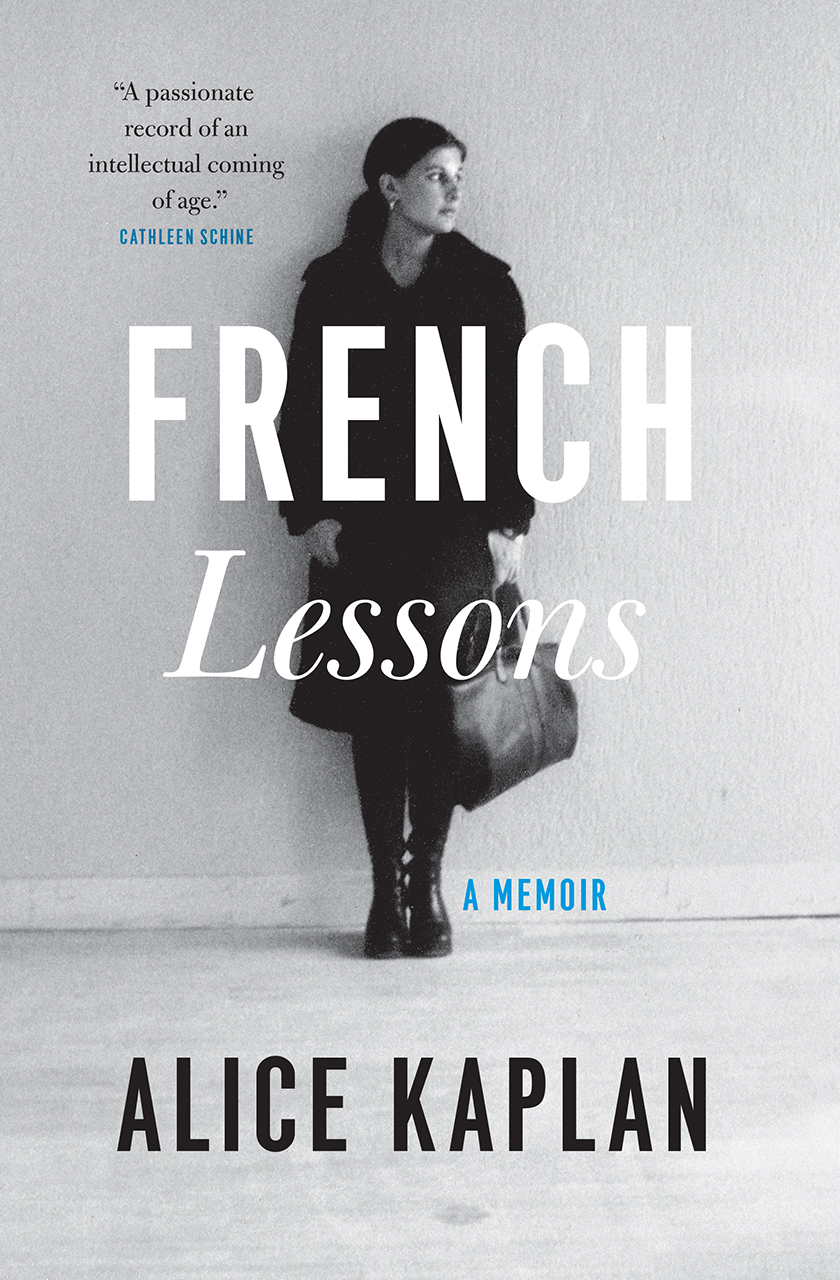

Analysis of the Book ‘French Lessons’ by Alice Kaplan

- Authors

- Name

- Yuxue Zhao

Catalog

- A Brief Account of My Impressions of the Memoir

- Analyzing Alice's Learning Journey from an Interactionist Theory Perspective

- Input Analysis: Alice's Learning Journey and Interactionist Theory

- Output Analysis: Alice's Learning Journey and Interactionist Theory

- A Personal Reflection on My Reading Experience

- References

A Brief Account of My Impressions of the Memoir

In "French Lessons," I followed Alice Kaplan's life journey, including her father's death, her mother's illness, and her bond with a French boy. French was her solace and a shield for her sorrow, evolving beyond a language to become a refuge and a core part of her identity. Her story resonated with me, from the initial anxiety in using French—like my feelings with English—to her meticulous language-learning methods that echoed my own. In the book, Alice provides a detailed account of her language-learning process, resonating with various theories. Her discernment of her grandmother's 'r' sound shows her innate language aptitude. Her determined efforts to engage in French conversations and her passion for French literature demonstrate the role of positive attitudes and motivation in second language acquisition. Her preference for dictation aligns with behaviourist principles. Nevertheless, the trajectory of Alice's French language acquisition is most consistent with interactionist theory, as evidenced by her immersion in a francophone milieu. In subsequent discussions, I shall undertake a detailed analysis of this congruence.

Analyzing Alice's Learning Journey from an Interactionist Theory Perspective

Input Analysis: Alice's Learning Journey and Interactionist Theory

Firstly, interactionists argue that linguistic input originates from natural language interactions with teachers, friends, or books. This input should focus on encouraging communication between the learner and others (Klein, 1986,p. 56). While attending a French school, Alice was fully immersed in a Francophone environment. For instance, she woke up to French news broadcasts (Kaplan, 1993, p. 47) and spent a year drawing and labelling “the world of Switzerland and French language” (Kaplan, 1993, p. 56). Furthermore, her travels in Paris enriched her understanding of French culture and customs. There, Alice actively sought French conversations, such as travelling with Mr. D, which led to her rich linguistic immersion. (Kaplan, 1993, p. 65-69).

Secondly, interactionists view an ideal learning environment as consisting of native speakers interacting with learners of the target language for social communicative purposes (Klein, 1986,p. 56). Alice's learning environment mirrored this; she was in an advanced French class with peers who had lived in French-speaking countries. In such a classroom setting, Alice found and overcame the challenge of the difficult French “r” sound (Kaplan, 1993, p. 53-55). Outside of school, her relationship with Andre provided a practical context for learning French, as they communicated in the language, and he corrected her pronunciation (Kaplan, 1993, p. 83).

Output Analysis: Alice's Learning Journey and Interactionist Theory

The interactionist theory posits that speaking naturally arises in communication with others (Klein, 1986,p. 56), corresponding to Alice's daily use and learning of French. She managed to buy gum effortlessly in French (Kaplan, 1993,p. 77), acquired medicine, and wrote love letters in French to Andre (Kaplan, 1993,p. 88), all driven by her authentic needs. Interactionists also believe that there should be no pressure to speak, except for a natural impulse to communicate (Klein, 1986,p. 56). Alice's language learning journey mirrored this, as she began speaking French after receiving sufficient input, driven by her intense interest and motivation for the language, which led her to actively seek speaking opportunities, like going to a village to buy tickets to speak more French (Kaplan, 1993,p. 53). Finally, concerning error treatment, interactionists maintain that errors that hinder communication are naturally corrected as meaning is negotiated, although some may require explicit corrective instruction (Klein, 1986,p. 56). For example, Alice learned word meanings by observing the facial expressions of her interlocutors (Kaplan, 1993, p. 48) and realized lexical errors through the pharmacist's laughter when purchasing mosquito bite medicine (Kaplan, 1993, p. 95). This suggests that Alice's errors were all discovered and self-corrected during her conversations. However, there were aspects of Alice's language learning that seemed to challenge the interactionist perspective. For instance, as a child, Alice displayed a natural sensitivity to language, intuitively grasping the meanings of Yiddish words by simply observing her mother's usage (Kaplan, 1993, p. 5). Furthermore, during her time in boarding school, she developed an understanding of the differences between verbs and nouns, as well as the proper placement of articles in sentences, all through passive exposure to her German roommates' conversations (Kaplan, 1993, p. 48). These examples appear to be more in line with the innatist theory, which posits that children have a special, inherent ability to deduce and understand the fundamental rules of a language system from natural language examples around them. This natural endowment is often referred to as “universal grammar”(Lightbown & Spada, 2021, p. 48).

A Personal Reflection on My Reading Experience

What impressed me most in understanding language acquisition was Alice's high motivation to learn French, a motivation that stemmed from a self-protective mechanism—her desire to hide behind French to avoid facing sorrow. “I had learned a whole new language at boarding school, but it was a language for covering pain, not expressing it” (Kaplan, 1993, p. 58). I was amazed by the profound impact of Alice's motivation. Under its influence, she persisted in practicing the 'r' sound, actively sought opportunities to speak French, dated a French boyfriend, explored French culture and literature, and became a professor of French at Duke. This has deepened my understanding of the importance of motivation in language learning, as Alice said, “Whatever the method, only desire can make a student learn a language, desire and necessity” (Kaplan, 1993, p. 131). Alice's experiences at the South State School resonate with mine. We both encounter unprecedented language mistakes such as letters that didn't exist, and words that bore no relation to any language (Kaplan, 1993, p. 165). I volunteer at a welfare organization as an English class assistant, where my role includes explaining and demonstrating whenever learners are unclear about the class content or instructions. Communicating with learners who are nearly illiterate often leaves me frustrated because I struggle to find simpler English words to express basic concepts. It feels like there’s a glass barrier between me and these learners; we cannot hear each other. This has led to self-doubt about my teaching abilities. I previously believed I excelled at teaching basic English to low-level learners; now, I realize that my strengths may lie in teaching children. The methods for teaching English to children and adults are quite distinct, even when the content is similar. Listening is emphasized throughout the book, as Alice points out that her linguistic enlightenment stemmed from listening, recalling, "Now, looking back at my childhood as the French Professor I've become, the first things I hear are scenes of language" (Kaplan, 1993, p. 5). This highlights the significance of sound interaction in her language learning. Her experience aligns with Underhill's(2005) philosophy of "Learn sounds not symbols" (p. x) and Gilbert's (2008)description of spoken communication as organized by "musical signals" (p. 2). Micheline likens speech to a "song," suggesting the profound potential of prosody in language learning, which has led me to a deeper consideration of the role of prosody in language.

References

Gilbert, J. B. (2008). Teaching pronunciation: Using the prosody pyramid. Cambridge University Press.

Kaplan, A. (2018). French lessons: A memoir. University of Chicago Press.

Klein, W. (1986). Second language acquisition. Cambridge University Press.

Lightbown, P. M., & Spada, N. (2021). How Languages Are Learned 5th Edition. Oxford University Press.

Underhill, A. (2005). Sound foundations. Macmillan Education